I had been secretly hoping the reason for our long wait for the Rose Review was that Lord Rose was insisting on it fitting on the back of an envelope. Once I’d overcome the disappointment of finding 68 pages though, well, I think it’s the most useful review we’ve had for ages.

In his observations Rose is tactful without pussy footing, and friendly while forthright. Indeed most of the observations have a feeling of freshness about them, even as they address issues most of us are familiar with. Why? Because he focuses on the one thing that almost no-one else does. More of that in a minute.

He and I got off on the wrong foot: ‘the Review aims to make people better qualified to manage and lead, p5’. Oh no, I thought, not again. But, reading on, I found myself thinking ‘no, he really gets this. He understands how to manage people and he’s looking afresh at the NHS: friendly but not dewy eyed, thinking clearly but practically. He’s not a Robert Francis. He’s worked with real people managing real change, he’s put things into practice. He’s not McKInsey.’

I liked his expressed surprise: ‘It is striking that the NHS has a central resource for quality but not for people.’p5. His sympathetic concern: ‘The NHS is one of our society’s proudest achievements but the challenges it faces could hardly be more daunting’.p7.

The kinds of people he has worked with are different though, and he doesn’t take enough account of that. This means his definition of leadership needs to be amended (as I’ll show shortly). But his overall emphasis on helping people throughout the organisation to be best they can be is music to my ears. I’ve said this so often and for so long that it feels so familiar and yet it is still almost completely lacking in training programmes, in organisational systems, in NHS culture. Its not that it has been driven out by constant reform –in my experience, except in isolated pockets, it has simply never been there.

So his emphasis on excellent people management may seem overly simple to some, but is actually radical (radical: affecting the fundamental nature of something; far-reaching; thorough).

I enjoyed his use of the term ‘performance management’ – rescuing it from our own debased usage and restoring it to mean the managing of people and how they are performing – and his insistence on having ‘proper time set aside for that’. And as for the thought of ‘a concerted effort to help people give and receive praise, encouragement and advice’ and ‘feedback that is constructive and thought provoking’, well it’s what I’ve spent the last thirty years encouraging.

This fits so well with what I personally believe: that what we need is much more good practical day-to-day management at every level: the everyday conversations that support, challenge and enable people to become the people they want to be. I’ve always called this ‘real management’ and I like Beverley Alimo Metcalfe’s term ‘nearby leadership’. If we had this in place at every level we would find organisations readily leadable, really manageable. If we think top down and focus on finding leaders for organisations before we put in place these day to day practical conversations we fail – we have tried this too often.

And Rose knows this. He seems to feel the need for it in ways that other observers have not. Here he is:

Performance management means thinking about how best to train, equip and assign the right people to the right roles. Done well it improves organisational performance. In the NHS it means something negative, It should mean a communication process that occurs throughout the year between manager and employee to support both the employee’s and the organisation’s objectives: a regular conversation on an individual’s career development.

Here is the Iles version!

The one thing he doesn’t get – or get sufficiently – is that the people he has worked with are different. The dynamics of retail or manufacturing organisation are different. Henry Mintzberg captures this neatly in his distinction between connected and disconnected hierarchies. I use and explain this here.

Doctors hold high social status, they are not sales staff; in the lengthy (important) process of acquiring their professional identity they are given very little insight into the nature of organsiations and how to behave productively within them. In the ignorance that comes of their separation from other students and careers they can make inappropriate judgements about the performance of others, and ascribe ill motives to those who are simply fulfilling a different role. Crucially, too, they have never been taught the skills to engage in these all-important supportive, challenging, enabling conversations. This is a tragedy-for them, for patients, for taxpayers. And it needs to be remedied.

The usual response is a call for ‘leadership’ and indeed Rose includes that here (to be fair that was his brief!). But what these behaviours mean in practice is that an emphasis on leadership and leaders is not enough: there is a corollary need for followership. Without followers leaders are useless: literally: they have no use.

So any effort on leadership needs to be twinned with persuading and enabling clinicians to respond constructively to challenging circumstances, to take collective responsibility for outcomes, to reflect with others on how to redesign services to make the best use of resources and achieve the best outcomes for patients -instead of self righteously, complacently ignoring the wider picture.

In short we need to develop followers, supporters, and I suggest the skills and attitudes and insights required for followership are almost identical to those of leadership –including one important component that doesn’t get mentioned enough in the leadership literature: the willingness/preparedness to recognise another’s authority in particular circumstances. But we also need a helpful understanding of what leadership involves.

Rose supports the list of characteristics in the Francis report of 2013 ‘visibility, listening, understanding, cross boundary thinking, challenging, probity, openness and courage’ and especially applauds the ‘ability to create and communicate vision and strategy’. I dislike this list. First because it lacks any sense of supporting and enabling. Second because ‘creating and communicating vision and strategy’ here carries the sense of broadcasting not listening. I’ll come back to that later.

So lets use a more engaging definition of leadership and then foster these skills in everyone not only a few. On page 22 Rose gives a list of the people who need to be involved in developing innovative care models: ‘porters, receptionists, nurses, consultants, specialists, technicians, therapists, GPs, service commissioners and many others’. He uses the list to make the case for a ‘single vision effectively communicated and understood by all NHS staff’ – I would use it as an illustrative list of those we need to help to become leaders and followers

Indeed if we add talk of following or supporting wherever Rose talks of leading his observations become even stronger and more relevant than they are already.

Try it yourself here:

‘…….a greater focus on the whole NHS workforce and on developing the talents and skills of its future leaders: they need to be better prepared for the daily challenges of leading [and supporting] a Trust, a ward, a clinical or specialist group, or a CCG’.

‘A lack of cohesive leadership [and followership] will produce an organisation where relations between staff and patients are merely transaction, doggedly contractual, obsessed with data and lacking in innovation and inspiration’. P47.

Strong and capable leadership [and followership] is key to doing transformational change.

More support is needed for leaders [and supporters] to develop large-scale change management, strategic and commercial skills, to be able to lead in a networked or group structure. P24.

Don’t these change? Instead of feeling ‘if only’, don’t you feel ‘let’s do it’ ?

And what about this:

‘Imagine an organisation where everyone understands and values the role of others, however seemingly small; where the main effort is clear; where local variations can apply without bureaucratic censure; where people trust each other and seek to be trusted; where delegation, training and personal and professional growth are seen as aspects of the same thing. This is what an organisation with effective leadership [and followership] look like. It is an organisation equipped both for long term planning and also for the immediate uncertainties and complexities required of any group of people (especially a large one) that seeks to provide the full range of health care to a large and changing population’.

Add ‘and followership’ and it stops being merely inspirational, it becomes aspirational: something we could actually achieve.

Why do we consistently fail to attend to and develop followership skills? As they are so similar to those of leadership and require the same courage and commitment we surely have the expertise to do so – because it requires us to do what we always shy away from – truly engaging with clinicians.

Instead, as Rose notes:

‘There is no underlying ethos across all disciplines. Not enough management by walking about and listening. The NHS remains stubbornly tribal’.

The three prominent staff groups …(Nurses, Doctors and General Managers) …often do not understand each other’s priorities. Despite the importance of clinical leadership a gulf remains between clinicians and managers: it can be hard to get clinicians to sit round a table and be accountable for the organisation as a whole. P47.

Sadly, as Rose’s experience (and that of his co-author Andrew St George) does not include disconnected hierarchies, the recommendations ignore this need for attention to followers and many are therefore irrelevant or unhelpful.

For example when it came to leadership ‘training courses’ and the need to monitor quality, pluralism and innovation (which was music to my ears), this then seemed to translate into perpetuating existing programmes that have ‘status, appeal and impact’. How disappointing.

If this kind of elite programme (where only the ‘best of the best’ are recruited so that they become the leaders of the future) were the answer, the NHS would be in a very different place today –because we have had these for decades. These undoubtedly advance individual careers. What they don’t do is impact constructively on the system. If they were the answer we would have seen the NHS anticipating change, responding to it effectively, harnessing the energy and enthusiasm of its 1.4 million employees, and not having to be dropped kicking and screaming into a world of (always) about 10-15 years ago. In any time period to date the factors that persuaded policy makers to invoke change should have prompted organisational leaders to do so at least 5 years earlier.

What we need instead is ways of finding the leader [ follower/supporter] in everyone, not badging a few. Everyone in or serving the NHS in any kind of day-to-day management role (which includes most professional frontline roles) should have access to excellent practical training in the simple hard behaviours of management.

There is a similar problem with the recommendations on a shared vision. I’m usually allergic to the term ‘vision’. In the Carnell/Nicholson view of the world that always seemed to mean ‘you do what I tell you, to sort out a problem I’ve defined, to reach a future I’ve decided upon’. But Rose seems to be using it differently, something like: one feeling, one hope, one driving sense of what it is about.

‘An agreed shared vision would give the NHS a united ethos and a consistent approach to getting things done’.

But would it? Could it? What would have to be different for that to happen? Because its been tried before, in the Constitution, in the 6 Cs, and others. This needs to feel real – not hollow. How? I’m not sure. I’d encourage people to talk about what mattered to them – as part of their performance management (supporting, challenging, enabling) conversations. I don’t think a vision is separate from performance management, or something that is attended to first, each is the way in which the other is brought about.

In other words it couldn’t be imposed, it would have to be found – from the frontline, from patients, from people managing and allocating resources: real people receiving and delivering real services. then it could be exciting and energising, and Rose is right to want it. But by the time this is translated into the report’s recommendations it becomes:

R1. Form a single service-wide communication strategy within the NHS to cascade and broadcast good and sometimes less good news and information as well as best practice to NHS staff, Trusts, and CCGs.

R2. Create a short NHS handbook/passport/map summarizing in short and /or visual form the NHS core values to be published, broadcast and implemented throughout the NHS’.

See what I mean?

However some of the recommendations do reflect the spirit of the earlier observations. My heart sang again at the thought of ‘a concerted effort to help people give and receive praise, encouragement and advice’. And I whole-heartedly support the wish to ‘review, refresh and extend’ the NHS graduate scheme. I chuckled at the need to recommend that managers should be supported as they progress (der…!). And how wonderful if we had ‘a cadre of capable, trained, current managers from all disciplines and with greater cultural diversity to better reflect its staff ‘– though why ‘better’??? Can’t it wholly reflect its staff? At all levels we need people who can see the organisation and its care through the eyes of their front line.

As for training to enable Trust boards to become a cohesive group of leaders, that sounds spot on – as long as it is not about ‘governance’, NHS finance etc. What boards need is an understanding of the behavioural dynamics that frustrate progress, they need to know how to add value, and how to meaningfully lead the organisation by liberating its people and gracefully holding it and them to account.

And a 90 day training cycle to support the brave idea that ‘people must be equipped for the changes the NHS has asked them to make’ seemed an excellent model.

How about the ‘central body coordinating training effort and resources’? If what Rose means is a shared, stretching ambition for management development then making HEE responsible for this seems right to me. All the fact based, clinical content of training programmes has to be brought to life in encounters with patients and colleagues, and I see the simple hard of managing, leading and following as the way in which we behave any plans and ideas into life. So this surely has to be an integral part of all other learning. If all HEE commissioned programmes included this element we could transform patient experience, and tax payer concerns, and help staff of all kinds to flourish.

So we need to be cautious about some of the recommendations but reflect thoughtfully on the observations and reflections.

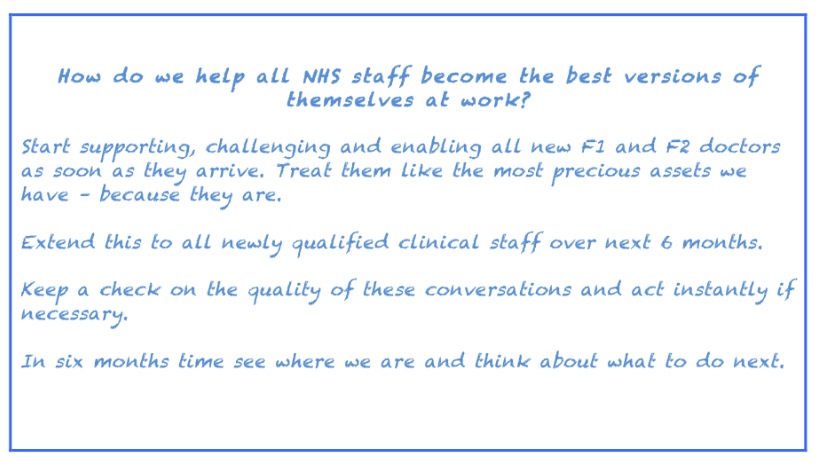

What would happen if we did that? Suppose we asked people to come up with their own approaches to the perceptive reflections of a man with truly valuable experience? Suppose we asked all sorts of thoughtful observers, people not so immersed in the NHS that they fail to see it clearly, to develop their own approach to Rose’s most important question: How do we help all NHS staff become the best versions of themselves at work?

What would your reponse be? What would mine?

Well I’d start without a report. I’d start tomorrow (literally – this is August). I’d start with the F1 and F2 doctors starting work in NHS hospitals. I’d make them the top priority for excellent ongoing support and challenge.

I would give them either:

- brilliantly facilitated action learning/coaching /mentoring sets, or

- one-to-ones with the people in the organisation who have the best people management skills (not doctors unless they have had excellent training and real aptitude for this),

and ensure they learn how to:

- make the most of the opportunities that face them

- work constructively with the people around them

- help the organisation help them to be as effective as they can be

- identify legitimate concerns and express them

- recognise unhelpful behavioural dynamics and influence these,

- and generally how to behave their ideas, their wishes, into action.

In the same way I’d get them

- sharing good practice and taking an active and constant interest in where it is to be found

- thinking from a patient and public point of view, and

- thinking about how they can use their own expertise to empower others.

In the next few months I’d offer the same to all new nursing staff and AHPs, and perhaps eventually to all new staff. Why new staff? Because these are the leaders and followers of tomorrow, these are the people we currently alienate within their first few months. When we neglect their welfare, ignore their suggestions and concerns, and deny them the constructive feedback to help them to grow, we breed a new generation behaving as frustratedly and unproductively as their forebears.

In this way we could build a demand for good management (performance management in the Rose sense of the term) – with doctors leading the way in insisting on their entitlement to those conversations that support, challenge and enable them to be the best clinicians they can be.

Would this fit on the back of an envelope?

I think Mintzberg might approve, I hope Rose would as well.

I think Mintzberg might approve, I hope Rose would as well.

Firstly, thank you, Valerie for another detailed and well-argued analysis. I too like to dwell on reports for some time before coming to a conclusion. I have tweeted about Rose and linked to various commentaries upon it and even highlighted some memorable soundbites from it but until now haven’t made up my mind about it. Your piece has helped me to put my thoughts in order and draw out my position.

When I first read the Rose Review what struck me was its almost polemical language, so different from the weasel words which most committee reports come out with. He really was hard hitting and for once didn’t settle on just one target but many. From the historic poor quality of line management to the degree of interventions and disempowerment emanating from Whitehall, he judged us all and found many wanting. Like you, I found this approach refreshing and exciting. Yes, he got it.

But again like you I found the remedies he proposes to be nugatory. He diagnosed our problems well but prescribed the wrong medicine.

I particularly like your suggestions for a new approach to developing leaders and followers, a subject dear to my heart. I think the 30% vacancy rate at acute CEO level speaks more eloquently of the failure of the” hero leader” than anything I can say. We need a new kind of leader, ones who’re skilled at supporting others and encouraging performance management throughout the organisation. We have enough confident decision makers. They’re what have got us where we are now. If we want to manage health and social care better in the future we need to try something different. I think the Leadership Academy has got this too, although followership seems to be a way off their agenda.

Your final proposal, to harness the power of the new professionals at the start of their careers should be a clarion call to all interested in culture change in the NHS. I hear that 160,000 people are studying to be part of our future health care workforce, mostly within the NHS. They should be the focus of our attention. Rather than see how quickly we can institutionalise them, we should be helping them to help us be different. In particular, we should aim to create in them the absolute demand for better support, better performance management and better leadership from the organisation. If we want to crack the “going over to the dark side” thing we need to catch people early. Help them see how integral to being a great professional being comfortable managing and following and leading is.

Well done, Valerie, your back of the envelop prescription is worth a go.